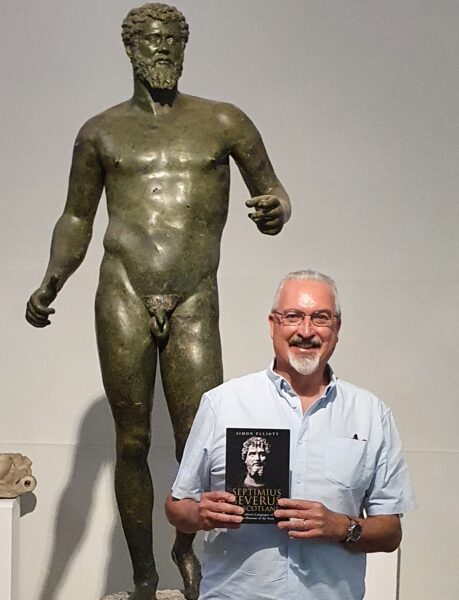

October is Black History month, and ahead of his forthcoming talk at Malton Museum, Dr Simon Elliott FSA has written a guest blog exploring what it meant to be a Roman of African heritage, Race in the Roman Empire, and Septimius Severus’ fascinating life and achievements.

Septimius Severus was the Roman Empire’s African emperor. Born in the blazing heat of a Libyan spring in Leptis Magna in AD 145, his story arc is truly astonishing, ending with his death in the freezing cold of a northern British winter in York in February AD 211. His career is one of superlatives. Ruling at the height of Roman military power, he commanded more legions than any other emperor. Further, under his rule permanent Roman territory was expanded to its greatest extent. Given this martial prowess, I argue in my new full biography that he was the most powerful person ever born in Africa, based purely on military and political agency.

The legions certainly played a key role in his story. Across its vast territory the Roman empire was always at war.

Even in times of relative peace, which were few in Severus’ reign, conflict could always be found. He understood this better than most, in his case from the very beginning of his reign when he rose to power at the point of a sword in AD 193, the last man standing in the ‘Year of the Five Emperors’. Severus never forgot his military roots, famously telling his squabbling sons Caracalla and Geta on his deathbed to ‘…be of one mind, enrich the soldiers, and despise the rest.’

African Heritage and Race in the Roman world

Throughout his life Severus stayed true to his African heritage. Dark skinned, he ensured he was portrayed this way in contemporary portraiture. While in his time this was unimportant in what was a largely Mediterranean empire, in our world today it can be.

I address this directly in my new book with the opening chapter, Identity and Race in the Roman World. The facts here are simple. Severus’ father’s line was Punic, so originally Phoenician colonists in North Africa from the Levant. His mother’s line was Italian. Severus seems to have favoured his Punic lineage. For example, even in politest Roman society amid the patricians in the imperial capital, he chose to maintain his strong North African accent. Then, once in power, he swiftly promoted North Africans at every opportunity to key positions of authority.

This is not surprising given, as I have seen in my own frequent research trips across the region, this was the richest part of the empire, with a proud cultural heritage to match anything in Rome, Athens or Alexandria. Severus used his North African upbringing as the template for what I style the Severan reset, this the first major post-Augustan reformation of the Roman world. It established the Severan dynasty which lasted over 40 years. Such was the scale of this reorganization, which some go further and call a hostile takeover, that it was not repeated again until the accession of Diocletian over 90 years after Severus became emperor (see below).

“Not a shy man”

Meanwhile, Severus was not a shy man, monumentalising his rule across the empire at every opportunity. He visited, and fought in, every region.

When he did, he left a mighty legacy in the built environment. Many of these sites I have visited personally, following in the footsteps of his travels. Intriguingly, given the popular focus on the likes of Julius Caesar, Trajan and Hadrian, this urban Severan legacy often hides in plain sight, with few aware of it. Yet the high-profile examples are many in number.

Think of forum Romanum in Rome where much is Severan, as are many surviving areas of the imperial palace on the Palatine Hill, the monumental Baths of Caracalla (which would have been called the Baths of Severus had he lived to see the enormous bathing complex completed) and the lovely Temple of the Vesta. Elsewhere in Europe, the presence of Severus is writ large from east to west.

Even in far off London, provincial capital of troublesome Britannia, the land wall that still defines the City today is Severan, while in York one can actually stand close to where he perished in the legionary fortress praetorium, now the undercroft of today’s York Minster. Meanwhile, in his native North Africa, every city and town I have visited has a highly visible Severan phase, whether in the soaring snow-capped Atlas Mountains or along the arid Saharan fringe.

Family ties

The story of Severus also features a dramatis personae fit to dazzle any historical epic. Think of Marcus Aurelius, the philosopher emperor, and Commodus, his mad and bad son. Then Publius Helvius Pertinax, the son of a manumitted slave who became Roman emperor and was Severus’ friend and mentor. Next Decimus Clodius Albinus and Pescennius Niger, British and Syrian governors respectively, and Severus’ former brothers in arms in the Marcomannic Wars. Both were destined to fight him tooth and nail for the throne in epic confrontations across the empire. Also Didius Julianus and Flavius Sulpicianus, scandalous bidders for the imperial throne when auctioned by the Praetorian Guard, truly one of the lowest points in imperial Roman history.

Then, last but not least, his own family. Foremost was Julia Domna, his second wife and love of his life.  She was a leading figure across the Roman world in her own right, and together they were the power couple of their age. Finally, their two sons, the psychotic Caracalla and unfortunate Geta, destined to live a spiral of bitter rivalry ending in the most sanguineous way within a year of Severus’ death. Here, the former had the latter murdered, he bleeding to death in Julia Domna’s arms.

She was a leading figure across the Roman world in her own right, and together they were the power couple of their age. Finally, their two sons, the psychotic Caracalla and unfortunate Geta, destined to live a spiral of bitter rivalry ending in the most sanguineous way within a year of Severus’ death. Here, the former had the latter murdered, he bleeding to death in Julia Domna’s arms.

Sadly that set the tone for the rest of the Severan dynasty. Caracalla himself was assassinated while relieving himself against a tree in AD 217. Macrinus (not a blood relative but a short-term usurper when Praetorian prefect) was then executed, Heliogabalus assassinated with his mother, and finally Severus Alexander also assassinated with his mother. Such was the grim end for the dynasty of which Septimius Severus was very much the high point.

What followed was the ‘Crisis of the 3rd Century’ when the empire almost imploded under the weight of numerous civil wars, usurpations, foreign invasion and plague. It then took another strong man emperor to drag the Roman world kicking and screaming back from the brink, this Diocletian who acceded to the throne (again at the point of a sword) in AD 284. I feel sure Severus himself would have greatly approved.

Leave a Reply