Fortlets might not sound like they are really up to much, although these strategic defences were very well built structures that were essential in defending Roman Britain from many attacks.

During the late 4th century Roman Britain was being attacked from land and sea by the Picts, the Attacotti, the Scots, the Franks and the Saxons. The historian Ammianus Marcellinus paints a picture of a chaotic situation with bands of raiders wandering around unchecked, taking prisoners and loot where they fancied, and destroying or killing at will.

In AD 367 the Emperor Valentinian dispatched a task force to try to get a grip on the situation, placing Theodosius (the father of the future Emperor Theodosius the Great) in command. Ammianus Marcellinus wrote that, on his arrival, Theodosius ‘rendered the greatest aid to the troubled and confused fortunes of the Britons’ including restoring ‘cities and garrison towns…and protected the borders with guard-posts and defence works’.

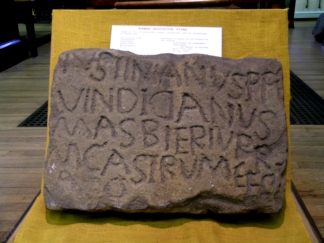

Along the Yorkshire coast a system of fortlets (often referred to as `signal stations`) were constructed. Archaeological remains of such structures have been found at Scarborough, Filey, Goldsborough and Huntcliffe. In 1774 a tablet was also discovered at Ravenscar bearing an inscription translated as ‘Justinianus the First Centurion and Vindicianus the Magistrate, built this tower and fortification from its foundations’ (Figure 1). The original series of fortifications might have included examples at Seaton Carew, Whitby, Flamborough Head and Spurn Point too.

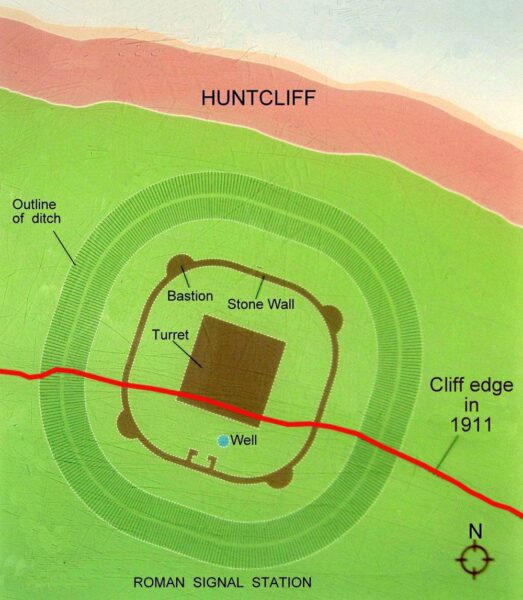

The fortlets consisted of a central tower within a small courtyard surrounded by a perimeter wall (incorporating bastions and a gatehouse) as well as a ditch with rounded corners (Figure 2). The excavations at Huntcliffe in 1912 revealed two particularly substantial bastions and a defensive wall (Figure 3).

The remains of the Scarborough fortlet are located on the headland of Castle Hill and can still be visited (Figure 4). It is estimated that the central tower was 30 metres high and the stunning views out across the sea are still evident today.

The fortlet at Filey was positioned on Carr Naze but, since Roman times, the area has been badly eroded. However, five large stones were recovered from the site in 1857 and placed in Crescent Gardens where they can be found in a flower bed. The heavy blocks (one of which is decorated with a dog chasing a stag) contain sockets that would have held oak pillars, perhaps supporting the first floor of the central tower (Figure 5).

Over the years there has been considerable discussion and debate about the function of the Yorkshire coastal fortlets. One suggestion is that they might have constituted a signalling chain – using beacons – monitoring movements and hostile activities along the coast. However, it would have required an enormous tower for Goldsborough to transmit any messages to Whitby, irrespective of the compounding effect of sea frets. An alternative may have been for them to communicate inland to forts such as Malton (via intermediate beacons), but it would still have taken some time for the military unit stationed there – Numerus Supervenientium Petuarensium – to mobilise and march to the coast or to intercept any raiders heading inland.

Others have proposed that the fortlets could have been places of refuge for isolated coastal communities against hostile forces. Both Goldsborough and Huntcliffe certainly had a good water supply with wells being found by excavators in their courtyards. Soldiers might have been garrisoned within timber barracks inside the walls with, perhaps, artillery being placed on the towers.

More recently Alistair McCluskey has argued that the fortlets acted as a deterrent by threatening a raiding party`s escape route rather than blocking its primary incursion into Roman Yorkshire. Given the nature of their substantial defences they would have been difficult for a small force to attack but, once any incomers had left their landing grounds, the Roman garrison could have simply marched out of the fortlets destroying any beached boats.

The Yorkshire coastal fortlets probably only enjoyed a brief period of Roman military use – perhaps, 20 to 30 years – before being abandoned. What happened to them next is a matter of conjecture but might have been somewhat gruesome. In the excavations at Huntcliffe fourteen skeletons of men, women and children were found dumped in the well. At Goldsborough, the archaeologists who uncovered the remains of the fort wrote:

‘In the south-east corner of the tower we made discoveries that can only be described as sensational. A short, thick-set man had fallen across the smouldering fire of an open hearth, probably after having been stabbed in the back. Another skeleton, that of a taller man, lay also face downwards, near the feet of the first. Beneath him was the skeleton of a large and powerful dog, its head against the man`s throat, its paws across his shoulders – surely a grim record of a thrilling drama.‘

Figure 1: Inscription from Ravenscar ©Whitby Museum

Find out more online: Whitby Museum

Figure 2: Plan of Huntcliffe Fortlet ©Creative Commons

Figure 3: Bastion at Huntcliffe ©Historic Environment Image Resource Database

Figure 4: Scarborough Fortlet ©Nick Summerton

Figure 5: The socketed stones at Filey. On the stone in the foreground a dog can be seen chasing a stag ©Nick Summerton

Can we find out how old was the installation of well? The water from the spring in the well was treated as sacred. You can find this in Prof. Nigro’s discussion on Motya … the Huntcliffe Forlet was a sacred site. The grounds are squarish and so is the ditch … you can find this in other mounds. The squarish shape is not as common as the round mound but you can find it.

The mound was an ancient fortress and temple. There may have been a pathway to the Wade’s Causeway … this was a ritual pathway.

The people that were killed there and thrown into the well were defending their temple. They were thrown into the well as blasphemy to their religion, if not, why bother to put them and leave them there .. then use the very same place later as a station fort. They could have been killed outright and trashed away.

They may have been elites and priests as well as their families. Priests and elites oftentimes hold the same status in ancient times. So their bodies may have NOT been removed by the Romans because such were held in high esteem by the people they were trying to subjugate. Caesar knew they were religious. Having their bodies have many implications.

Figure 5 – “dog and a stag” is reminiscent of the Hunt in Pictish slabs. This kind of art is known to us as “animalism” … it is a symbol of the Hunt … the natural right to rule.

It would be helpful if you could take a geophysical survey of the surrounding areas as well … you can see below the ground what on the surface was removed. From the formation, you can see if they follow the same pattern/same signature.

Thanks for your comments and thoughts. As our current blogs are based on volunteers carrying out research on each topic from other sources, and from their own knowledge, they are intended to give people a brief introduction to various topics, so we would need to research this further to be able to add any more detail.

What do you think about the possibility of a Roman Signal station at Flamborough?

Do you think there was one but it had fallen into the sea?

It’s almost certain that there was a fortlet (maybe even more than one) somewhere on the headland. These were probably intended to be bases for small mobile detachments of maybe 30 men, not ‘signal stations’, so didn’t need to be intervisible. Beacon Hill on the south side of the Head has been suggested as a likely site: it overlooks South Landing which would have been an easy place for raiders to land, being much more sheltered than the landing places on the north side and east end (there was a medieval harbour there). There was a much later beacon at beacon Hll as the name suggests, but Roman artefacts and rough stones were found before it was all unfortunately quarried away. Goldsborough has shown though that sites didn’t need to be directly next to the cliff, and the chalk at Flamborough has in any case survived much better than the unstable cliffs at the other sites, so an alternative site may exist and still survive.