Three hundred years ago it was suggested that a Roman road – Wade’s Causeway – ran from Amotherby over the Vale of Pickering and the North Yorkshire Moors towards the coast. There is also a long-held view that this military way traversed Fort D at Cawthorn and then descended from the escarpment, on which the Roman earthworks sit, to the valley of the Sutherland beck

In 1817 Rev. George Young, a local pastor wrote a ten-page description of Wade’s Causeway in his ‘History of Whitby‘ clearly describing the onward route between Cawthorn and the Roman Fort at Lease Rigg. But he also commented how ‘it is almost enough to break the heart of an antiquary, to see a monument that has withstood the ravages of time for sixteen centuries wantonly destroyed‘ to build banks or to repair ‘contemptible by-roads‘.

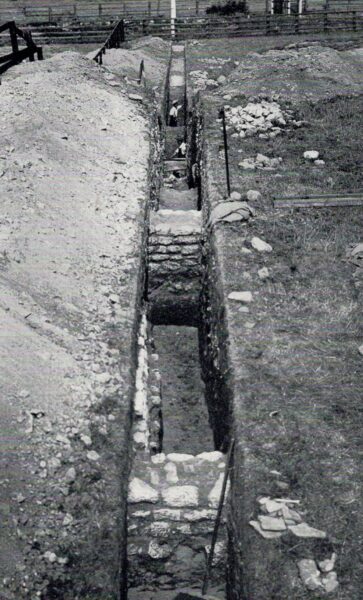

Nowadays a surviving one-mile stretch of this structure can easily be followed across Wheeldale Moor. It consists of flagstones seated on a cambered base of soil, clay, peat, gravel and loose pebbles forming a raised embankment varying between 5.4 and 6.7 metres wide. It is also crossed by a dozen small culverts and, in some parts, edged with kerbstones of upright slabs (Figure 1).

But is it really Roman? Some archaeologists have suggested that it could be a medieval road or a more ancient boundary feature. Aside from some pottery no Roman objects have been found on or near the structure across Wheeldale Moor. Also, a stone burial cist set into one side of the monument most likely pre-dates the Roman occupation (Figure 2).

Others have expressed concerns that it might have been ‘Romanised’ and ‘re-constructed’ by a local gamekeeper, James Patterson, who removed the peat thereby revealing the stones at the beginning of the last century. However, a careful assessment of Wade’s Causeway by Hayes and Rutter in 1964 concluded that it was a Roman road based on the following key findings:

- The raised and cambered embankment (agger), providing a well-drained road foundation

- The substantial layer of rough sandstone slabs (Figure 3)

- The kerbstones (Figure 4)

- The evidence of a surface layer of gravel

Also, a century before James Patterson’s work, Rev. George Young wrote that ‘the foundation is usually a stratum of gravel or rubbish, over which is a strong pavement of stones, placed with their flattest side uppermost, and above these another stratum of gravel or earth to fill up the interstices, and smooth the surface. To keep the road dry, the middle part has been made higher than the sides; and, to prevent the sides from giving way, they are secured by a border of flat stones placed edgewise’.

Admittedly some of the culverts crossing the road appear modern as do the ditches running alongside (Figure 5). There are also occasional ‘gaps’ where the structure crosses several streams but, perhaps, the gently rising banks at such locations originally bore wooden bridges (Figure 6).

Finally, if the monument on Wheeldale Moor is, indeed, Roman then was it constructed as a component of the early military campaigns across the North and/or to facilitate troop movements between Malton Fort and the coastal fortlets in the fourth century? There is no clear answer to this, and it has even been suggested that it was used by jet traders too.

Wade’s Causeway is an intriguing monument and considerable controversy still shrouds its origin and purpose. Local legend also tells of a giant named Wade who once lived in the area. He is said to have built the road for his wife, Bell, to herd her sheep along en route to the moorland pastures or to market.

For more information on Wade’s Causeway visit: Wikishire.co.uk

Figure 1: View of the possible Roman road crossing Wheeldale Moor ©Nick Summerton

Figure 2: Stone burial cist set into the side of the possible Roman road crossing Wheeldale Moor ©Nick Summerton

Figure 3: Sandstone slabs on the possible Roman road crossing Wheeldale Moor ©Nick Summerton

Figure 4: The kerbstones edging the possible Roman road crossing Wheeldale Moor ©Nick Summerton

Figure 5: Culvert on the possible Roman road crossing Wheeldale Moor ©Nick Summerton

Figure 6: Suggested location for a wooden bridge on the possible Roman road crossing Wheeldale Moor ©Nick Summerton

Have you seen our other blogs?

https://www.maltonmuseum.co.uk/2021/04/17/the-romans-at-cawthorn/

https://www.maltonmuseum.co.uk/2021/03/06/petillius-cerialis-and-the-brigantes/

https://www.maltonmuseum.co.uk/2021/05/29/the-fortlets-signal-stations-along-the-yorkshire-coast/

https://www.maltonmuseum.co.uk/2021/02/20/roman-jet-and-the-malton-bear/