Roman Face Pots

Face pots are among the most intriguing, yet least understood, forms of Roman pottery. Prior to Gillian Braithwaite’s 1984 and 2007 research, they had received little attention. Face pot sherds are not in themselves uncommon, but there are relatively few surviving complete pots. As with most surviving Roman pottery, they are usually discovered at burial sites. Not all cultures produced them, and even then not throughout all periods; although the idea of anthropomorphic pottery is thought to be as old as pottery itself. Roman face pots are usually categorised as belonging to one of three groups: head pots, face pots or face flagons.

Mediterranean origins

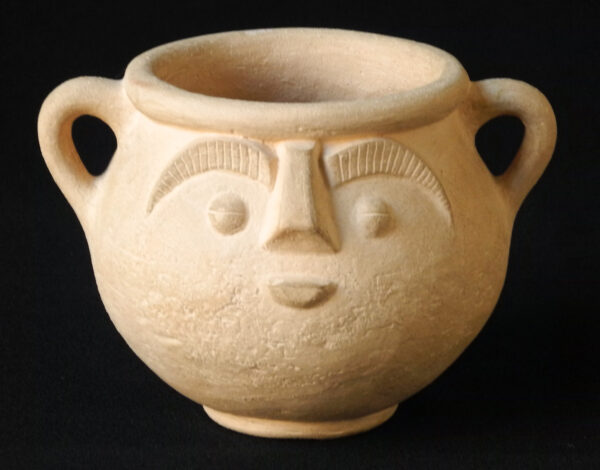

Roman face pots originated in the Mediterranean area as face beakers. These were the size of drinking vessels with the face ‘mask’ itself covering much of the pot surface. As the empire expanded, face beakers travelled north with the armies, eventually merging with the larger iron-age face-urn and face-jar traditions of the Rhineland where the face is situated on the upper shoulder area of the pot just below the rim.

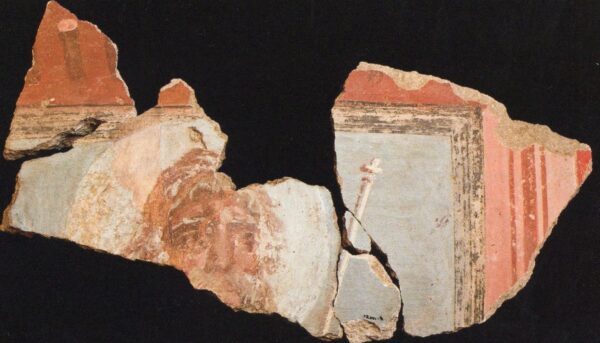

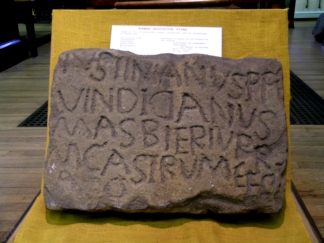

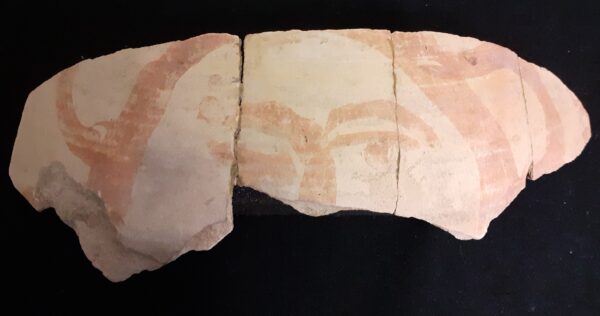

The facial features were applied to a traditional cooking pot or storage vessel. Faces were rarely painted directly onto the pot itself; although Malton Museum does have a face pot sherd where this is the case. Gillian Braithwaite suggests a painted face on a vessel of this size is unique.

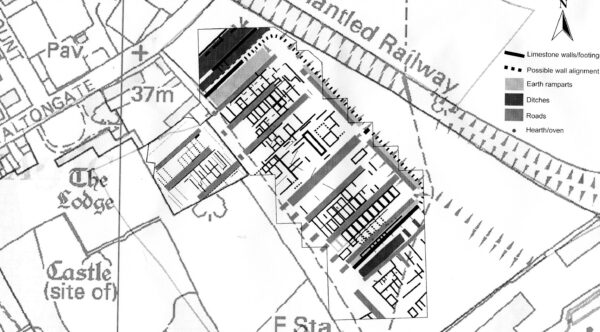

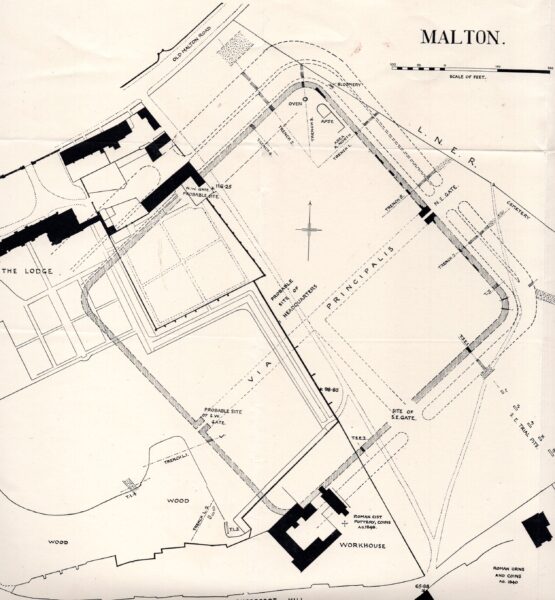

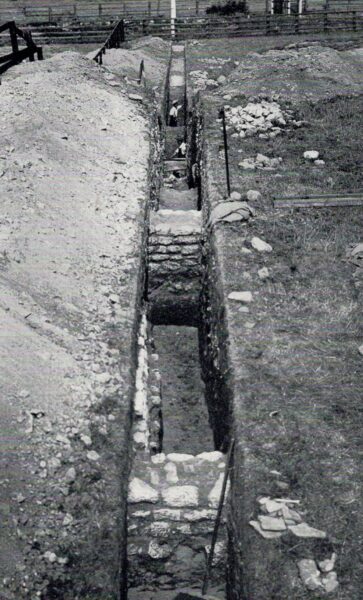

The Roman face pot arrived in Britain with the legions during the first half of the 1st century and continued into the 2nd and 3rd centuries. Face pots maintained a strong military connection throughout their usage. Consequently, Roman face pots are generally found in the footsteps of the army and are associated with the eastern and northern regions of Britain. If found elsewhere they can usually be traced to an original army presence.

Roman Head Pots

Like the face pot, the head pot is generally found in eastern and northern locations where the Roman military were present. Arriving in Roman Britain around the 3rd century, head pots share some clear similarities with the face pot, it also exhibits a number of differences.

Whereas the face pot is generally a domestic vessel with facial features applied to, or carved into it, the head pot took the deliberate form of a human head with the features formed from the pot fabric itself; often pushed through from inside the pot using exterior moulds. These facial features tend to be more realistic and classical, closer to the style of earlier Greek pottery. As the head pot evolved in Roman Britain its features took on the less classical appearance of the face pot. In fact Braithwaite refers to what might be called hybrid pots where the face ‘mask’ itself is formed in the manner of a head pot, but using vessels that are closer to those of face jars.

In the Yorkshire area Braithwaite suggests this hybrid form, with its almond-shaped eyes, became halfway between a face pot and a degenerate copy of a head pot and subsequently could be described as either.

Roman face flagons

The face flagon emerged at around the same time as the head pot but, like the face pot, was a conventional vessel (in this case a flagon, with or without handles)

with a complete face ‘mask’ added. The face mask itself is usually taken from a mould and applied to the upper neck, often raised above the rim of the vessel itself. The face is almost always female. Perhaps, in the view of some researchers, connected to female divinities such as Venus and emphasising the aspects of fertility and birth.

Whose faces are they and what were the face pots used for?

It is unusual for Roman pottery to be modelled by hand, as is the case with face pots, although the potter seems not to have been free to randomly create an image of their own choosing, but rather to have followed a stylised and schematic tradition. Pottery-kiln researcher Vivien Swan suggests some form of pattern book might even have been used.

It is generally accepted that Face Pots and Face Beakers, with their strong military connections, have a religious significance and are references to Bacchus; although the sheer variety of faces seems to rule out an attempt to portray any one particular deity. The fact that as many as 50% of finds in some areas are related to burials reinforces the religious connection, but even where domestic finds outnumber those in religious buildings it should be remembered that in Roman society houses, and even some individual rooms, had their own shrines.

Braithwaite suggests that as the head pot and face pot developed separately, with the head pot found less frequently in domestic contexts, the two probably had different uses and served different purposes. The face flagon may have a different use yet again. It may be too simplistic to assume that because pots share the portrayal of facial features they must have a similar use or meaning.

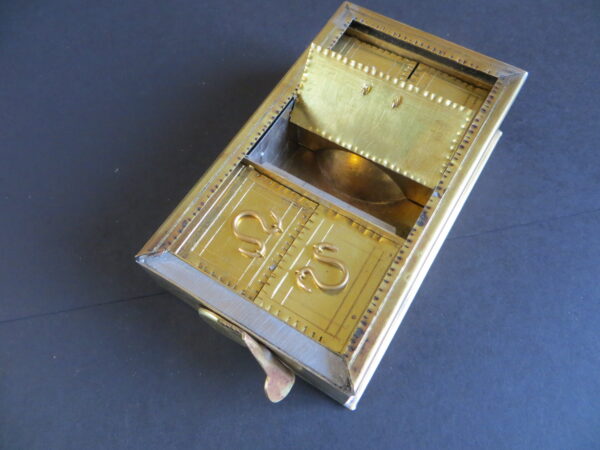

Connections to smith gods – deities of metal-working

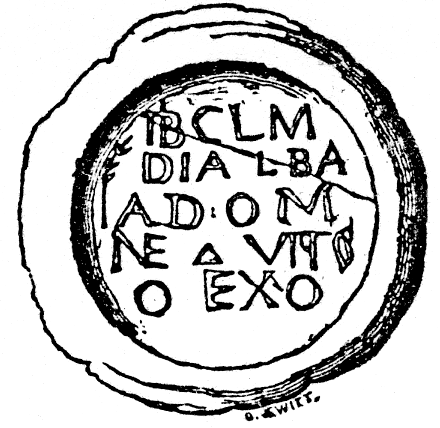

The face pots’ religious connection is supported by discoveries of face pots bearing symbolism linking them to smith gods. In common with most ancient cultures the Romans honoured a deity of metal-working – a smith god. Some Roman pottery carried representations of metal-working tools (such as hammers, anvils or tongs). The Romans were usually quite prepared for their gods to be assimilated with local deities, in this case the Celtic smith god with the Roman god Vulcan. In the Malton area particularly, pottery was made with both face ‘masks’ and representations of smiths tools applied to them. The practice of votive presentations to gods in this way, especially when appearing on the same pot, re-enforces the religious significance of face pots.

Any attempted explanation of the identity of the face pot faces, or their intended purpose, remains an educated conjecture. Unless there is a discovery of further evidence we may never know for certain; but, in the words of Gillian Braithwaite, ‘maybe one day’.