Most of us would probably consider that modern medicine and technology has brought about eye care, and that ‘Roman Eye Health’ and any treatments or remedies probably didn’t exsist – yet both archaeological, and written accounts tell us that such things certainly did exsist.

The health of the eyes was a particular concern in the Roman world. The eyes were considered a privileged body part and the transition point between the soul and the outside world.

Unfortunately, crowded bathhouses and the excellent communications afforded by the road network would have contributed to the spread of infectious eye diseases across the Empire. From Britain a military strength report of the First Cohort of Tungrians found at Vindolanda specifically categorises the thirty-one soldiers signed off as unfit into three distinct groups: aegri (sick; 15); volnerati (wounded; 6); and lippientes (eye troubles; 10).

Within the Roman medical literature there was a significant emphasis on the treatment of a variety of eye diseases using eye ointments – or collyria. For example, the first century doctor Scribonius Largus, listed twenty-two collyria and Galen, physician to the Emperor Marcus Aurelius over two-hundred. In addition, collyrium stamps are found throughout the Western Roman Empire and two dozen have been discovered in Britain. These would have been used for impressing the name of the maker, the remedy and the purpose of the treatment onto a newly manufactured collyrium (before it was left to harden). Work I have undertaken with the students at Malton School has demonstrated the remarkable effectiveness of many of these Roman medicines in treating eye infections.

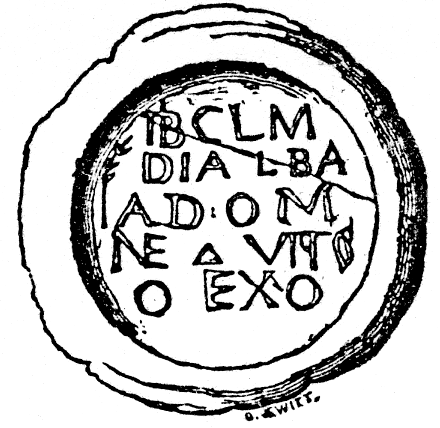

Typically, collyrium stamps are small square blocks made of greenish schist or steatite with wording on each of the four edges (Figure 1). In a few instances the stone is oblong with two inscribed sides and in one example from Wroxeter, the stamp is circular (Figure 2). The letters are cut in intaglio form and written from right to left so that when stamped on a soft collyrium they make an impression that reads from left to right.

Lippitudo (acute conjunctivitis) is the mostly frequently cited problem mentioned on the British stamps followed by aspritudino (chronic conjunctivitis). The example from Cambridge is inscribed:

L. IVL. SALVTARIS PE/NICILLUM AD LIPPITUD

‘the collyrium of Lucius Julius Salutaris, to be applied with a fine brush for lippitudo of the eyes‘

A collyrium stamp discovered in York (Figure 3) bears the letters:

IVLIALEXANDRI DIAMYADASP

‘Julius Alexander`s salve made from misy for aspritudo

Collyrium stamps may have been handed on from person to person and even down the generations. In an example from St. Albans the name Flavius Secundus is executed in a rougher style than that for Lucius Julius Ivenis suggesting a succession. Also, the green colouration of the stones was thought to confer some sort of magical property to the object.

Intriguingly collyrium stamps are absent from many areas of the Roman Empire and it has been argued that they relate to the different medical systems in Gaul, Germany and Britain at the time. Perhaps the sticks of medicament were prepared in bulk at a larger town – such as York, London or Colchester – for use by eye healers making regular circuits around the local countryside. In 1990 a Roman grave was found near Lyon including a brass box with four compartments that contained 20 baton-shaped collyria. Also discovered were three brass probes of the type used to mix medicaments alongside a worn slate grinding stone. It is likely that many travelling eye healers would have carried such equipment.

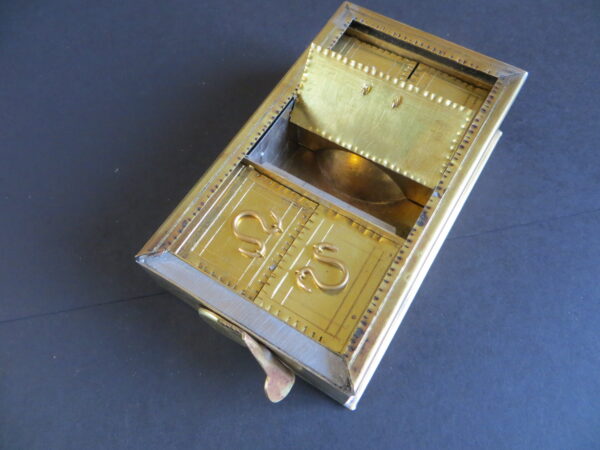

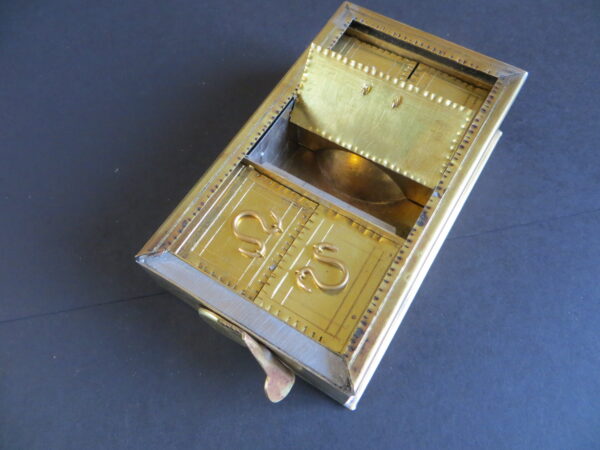

Stopping in a place such as Malton a peripatetic eye healer from York (such as Julius Alexander) might have pulled out of his travelling pack a brass medicine box. As the locals looked on the lid would have been retracted revealing five small compartments containing a range of embossed and hardened collyria (Figure 4).

A collyrium would then have been carefully selected according to the patient’s needs with a small piece being cut off. After crushing the collyrium fragment on a stone palate using a brass probe, the resulting powder would have been mixed with water, egg or milk as appropriate in the cup-shaped depression on the underside of the box to produce a paste for application to the eye (Figure 5).

Figure 1: A collyrium stamp from Kenchester ©The Trustees of the British Museum

Visit: The British Museum

Figure 2: A collyrium stamp from Wroxeter ©Nick Summerton

Figure 3: A collyrium stamp from York ©York Museums Trust

Visit: York Museums Trust

Figure 4: Reconstructed eye box with view of central compartment ©Nick Summerton

Figure 5: Cup-shaped depression on underside of reconstructed eye box ©Nick Summerton

[…] Notes on seals via Malton Museum […]

Thanks a lot for giving everyone an extraordinarily brilliant chance to read articles and blog posts from this blog.

Enjoyed reading this, very good stuff, regards .

Would love to constantly get updated outstanding blog ! .