Roman Jet, and the Malton Bear in particular, give us a fascinating insight into Roman life through some highly impressive pieces of artistic jewellery and charms.

The death of Prince Albert in 1861 marked the start of 40 years of mourning by Queen Victoria. It also led to a fashion for the wearing of black and jet jewellery across Victorian society. As an adornment jet had been largely ignored since enjoying tremendous popularity in Roman Britain during the 3rd and 4th centuries.

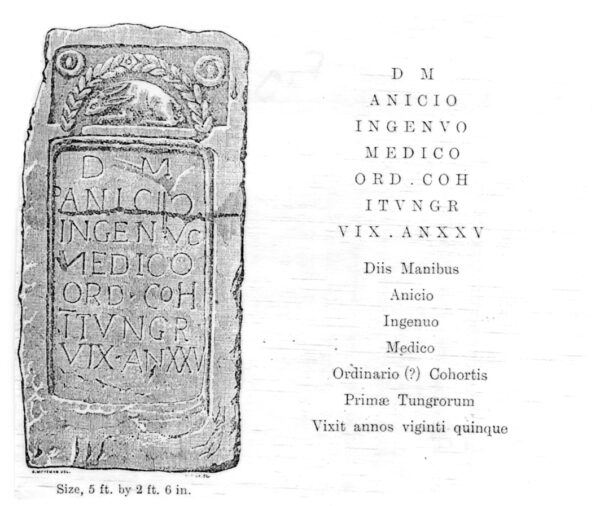

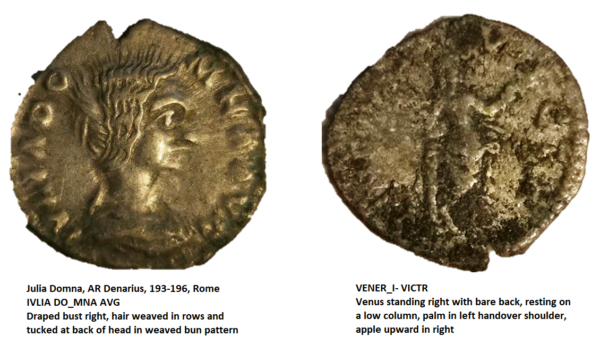

The beginning of the Roman interest in jet is associated with the visit of Julia Domna to York in 208 AD (Figure 1). She had accompanied her husband, the Emperor Septimius Severus, and their two sons, Caracalla and Geta, there prior to a campaign in Scotland. But it cannot have been a particularly joyous family gathering, especially as the only interests shared by the two brothers were reckless extravagance and fratricide!

Julia Domna had been born in Syria and her father was high priest in the temple of the sun god El-Gabal. In addition to being extremely well-read with broad interests in art, philosophy, religion and politics, she was also a trend setter. Her hairstyle was copied by individuals including the Empress Salonina as well as the Palmyrian Queen Zenobia, and it is said that she introduced the wearing of wigs into Rome.

It is quite possible that, during her time in Britain, Julia became fascinated by jet and captivated by some of the objects she would have seen in York. Intriguingly her name, Domna, is an archaic Arabic word meaning “black”, referencing the nature of El-Gabal which took the form of a black stone.

Although, today, we are aware of static electricity, there would have been something magical to the Romans about a substance that, according to the 3rd century author Solinus `detains things close to it when heated by rubbing`. Pliny also mentioned that, when burnt, jet could be used to detect malingerers or women masquerading as virgins, in addition to being able to drive off snakes.

Jet is a type of lignite, the lowest rank of coal, and the variety from Whitby is derived from the fossilised wood of an extinct species, not like our Monkey Puzzle Tree. Most Roman jet was probably obtained by beachcombing along the coast near Whitby, (Figure 2) being then transported inland to workshops at places such as York and Malton.

Several items of jet decorative jewellery have been unearthed in Malton including rings, beads, a spindle whorl and pins in addition to a splendid, segmented bracelet (Figures 3 & 4). Finds of numerous unfinished jet fragments and an incomplete lathe-tuned baton provides evidence for jet working at Malton.

The religious and magical associations of jet are evidenced by the finds of jet amulets carved in the shape of Medusa heads in graves of young adult females from Roman York (Figure 5). Such items were regarded as having the power to attract and hold evil powers thereby diverting them from other targets, such as the wearer. In some places jet pieces in the shape of animals have come to light – big cats, foxes, bears and eagles. Many of these carved objects exhibit evidence of rubbing too, perhaps to produce an electrostatic effect associated with various magical practices.

In 1929 a grave was excavated just outside the north-east gate of the Malton Roman fort. Alongside an infant skeleton was a jet bear, a jet bead, a copper alloy bracelet and an early 3rd-century coin (Figure 6). Despite missing its hind legs, the jet figure is an excellent model of a Eurasian Brown Bear, depicting the strong muscle hump behind the head (Figure 7).

Seven other jet bears have been found in infant burials from Roman Britain and it is suggested that they represent guardians placed in the burials to ensure that the child did not enter the underworld alone and unprotected, perhaps linked to the Greek cult of Artemis. The coins found with the jet bears from York and Malton might have been put there to pay the ferryman for the occupant’s journey into the underworld.

Figure 1: Denarius of Julia Domna, excavated at Brough in 2020 ©Nick Summerton

Figure 2: Jet from beachcombing at Whitby ©Geology.com

Find out more about Whitby Jet on ©Geology.com

Figure 3: Jet ring from Malton ©Malton Museum

Figure 4: Jet segmented bracelet from Malton ©Malton Museum

Figure 5: Jet Medusa pendant from York, Photographed by York Museums Trust Staff ©Commons:Licensing., CC BY-SA 4.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=38964856

Figure 6: Infant grave outside north-east gate of Malton fort ©Malton Museum

Figure 7: Malton jet bear ©Malton Museum