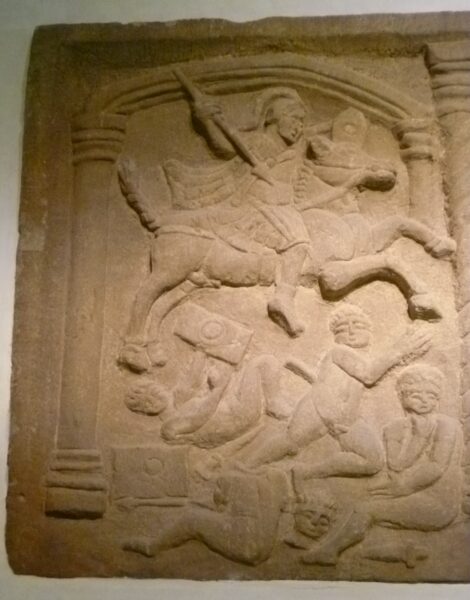

There appears to be a lot of grandeur associated with Roman cavalry, as we can see from some very finely decorated cavalry sports helmets – read on to find out more

Malton has enjoyed a long love affair with horses and racing. It was once dubbed the Newmarket of the North and, according to local legend, it was the Romans who first introduced horse racing to the town.

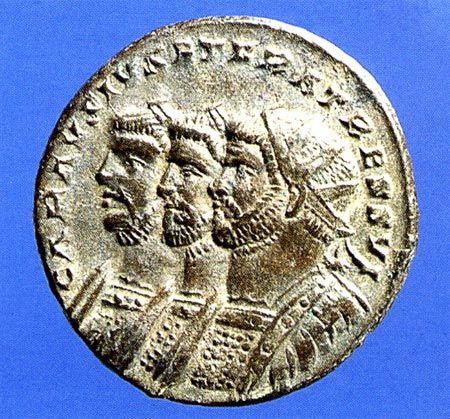

During the excavation of the Roman civilian settlement (vicus) in 1970, a dedication slab was unearthed (figure 1) dated to the middle of the second century AD. Parts of the lettering are missing, but the complete text probably read:

T or P (?)

CANDIDUS

PREF ♥ ALAE

PICENTIAN

D ♥ D

This is translated as `Candidus, prefect of the Ala Picentiana gave (this) as a gift`. Above the `C` there is also the bottom section of another letter, perhaps T or P, suggesting that Candidus was a cognomen (the third name of a Roman citizen).

Within the Roman Empire the ala were auxiliary units composed entirely of cavalry. The name is Latin for a wing and derives from the use of horsemen on the flanks of the army. Unlike the legions, the auxiliary troops were drawn from the free inhabitants of the Empire who were not Roman citizens, termed peregrini.

By the time of the Malton inscription, there were about 70 auxiliary regiments in Britain amounting to three-quarters of the military force on the island. In addition to eleven alae there were also auxiliary infantry cohorts and mixed units.

Originally auxiliary troops would have been led by their own local chiefs but gradually this changed with most ala prefects being Romans by the second century AD. Such individuals would have moved up the ladder of military promotion from, perhaps, a previous position as military tribune within a legion.

The riders of the Ala Picentiana were recruited from the inhabitants of Gaul, although Candidus would, most probably, have been born into a well-connected Roman family. The five-hundred strong unit served in Germany first before being transferred across to Britain. Stationing the ala at Malton might have been linked to the need to provide the 6th Roman legion (based at York) with a cavalry wing.

One reason for a trooper joining an auxiliary unit was to acquire Roman citizenship by serving for twenty-five years. Bronze diplomas were issued to grant such citizenship, with one copy being given to a veteran and another retained by the authorities. Just outside Sheffield a diploma was ploughed up in 1760 and refers to several units, including Malton`s Ala Picentiana. It is translated as `to the cavalrymen…who have served twenty-five or more years and have been honourably discharged, whose names are written below, citizenship for themselves, their children and descendants, and the right of legal marriage`.

Little digging has taken place inside the walls of the fort at Malton, but a geophysical survey has revealed double lines of barrack blocks. Based on excavations at the cavalry fort at Wallsend it suggested that the troopers occupied one range with their horses being stabled in the adjacent rooms.

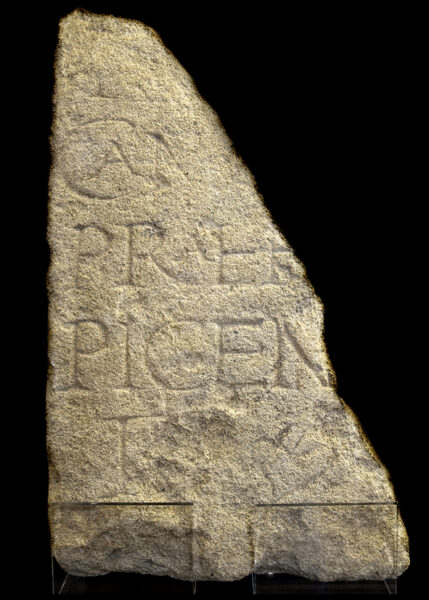

Roman auxiliary cavalry riders were usually heavily covered in armour and furnished with short lances, javelins, shields and long swords. Military strap fittings (from horse harnesses), a bone sword handle, copper alloy scale armour, chain mail and iron spearheads have all been unearthed at Malton. The Bridgeness stone (Figure 2) from the Antonine Wall (dating to the same period as the Malton inscription) portrays a fully equipped auxiliary cavalryman trampling and decapitating naked barbarians.

Within the Roman Empire ala units enjoyed considerable prestige and their members were also better paid than auxiliary infantry. Dressed up in parade armour – including splendid helmets of the type found at Ribchester and Crosby Garrett (Figures 3 & 4) – they would have put on spectacular public displays showing the skill and speed of the riders. Perhaps there is a lot of truth in the Malton legend about Roman horse racing!

Figure 1: The Malton Ala Picentiana inscription © Malton Museum

Figure 2: Detail of a legionary tablet c.142 AD found at Bridgeness. It shows a Roman mounted auxiliary trooper. ©Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

Find out more about the Bridgeness Slab on Wikipedia

Figure 3: Ribchester cavalry sports helmet, bronze. ©Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic

Find our more about Ribchester on Wikipedia

Figure 4: Crosby Garrett Helmet, a copper alloy Roman cavalry helmet dating from the late 2nd or early 3rd century AD © Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic